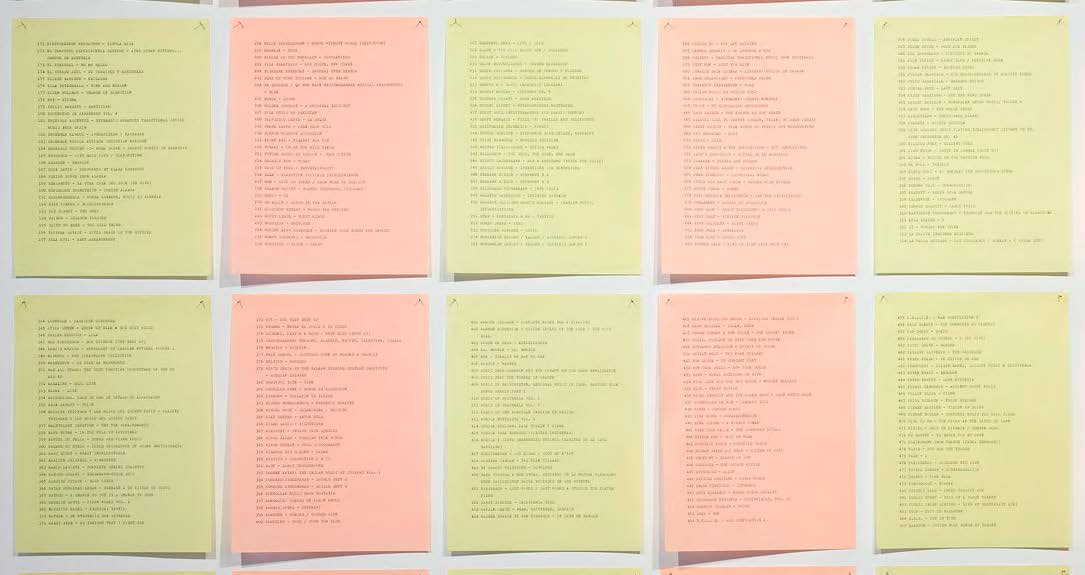

Public Image The iPod and the MP3 players brought forth the phenomenon of the “dematerialization” of music. Unlike LPs, cassettes and (even) CDs, music that is managed and stored from the computer is not tangible. In other words, although the information is deposited in hard drives, the users will never hold in their hands the booklet or case or cover of an album. With the arrival of Spotify and YouTube, this phenomenon has become even more radical: the information is no longer in our computers but on the Internet or “on the cloud”. But to speak of “dematerialization”, in reality, is a fallacy: all these contents, as our emails and Google Book’s digital libraries, are deposited physically within installations filled with servers, located in places of the world that we know nothing of. These contents do not actually “float in air”, they are kept in spaces to which we don’t have any access, located in private properties, far from public scrutiny. Also, a certain subscription grants access to these platforms (a commercial-free access) but the files never reach our hands or our hard drives. The Internet era, on the other hand, is the era of the information overload: if back then it was almost impossible to acquire certain book or CD, now the phenomenon has reversed: there are so many that we cannot listen to all of them; but we continue to overload our hard drives with music that we will never listen to and with PDFs we will never read. The immensity of Spotify’s software generates a feeling of being lost, not knowing which song to listen to…Internet is so big that it is like having everything and nothing at the same time. Against these corporate policies and contrary to the idea of a non-navigable file, Israel Martínez began to materialize the music contents that he listened to on the Internet. “Imagen Pública (autorretrato)/Imagen Pública (self portrait)” is an installation composed of 666 cassettes that enclose diverse albums downloaded from Spotify, YouTube, Vimeo and other digital platforms like blogs and websites from which users can download music. In order to identify the content of each cassette, Martínez generated an index patiently typescript on yellow and pink bond paper sheets, imitating the covers of the cassettes that “El Indio” sold at Imagen Pública. At first, Martínez began to recuperate punk, hardcore and alternative music albums that he once owned and had lost throughout the years but he soon decided to record other kind of music gender, specifically music from different regions of the world. So, next to Eskimo songs from Alaska, Eskorbuto, Pakistani songs, the Lebanese renaissance and the Turk vanguard, in this inventory we can find experimental music, jazz, rockabilly, surf, bel canto, classical music, Baroque, corridos, rancheras, boleros, reggae, Flamenco music, glam, post-punk, fado…except one hit-song by Madonna, we won’t be able to find those big commercial names of the Pop industry. The display of the cassettes in the exhibition space, piled one on top of each other, remind us of a body of buildings. This is the result of, on one hand, Martínez’ ongoing research and documentation of housing models brought forth by communist governments in Eastern Europe (“Comunies”, a work in progress by the artist) and, on the other, of the artist’s desire to point to the fact that sound is the main substance in the relationships that are interlaced in a building or within a city. Unlike CDs or digital files, magnetic tapes are not “burnt” or “copy-pasted”: in order to record these cassettes, the artist had to listen to each one, from the beginning until the end, in a sort of private and discontinuous performance that lasted 666 hours. This necessarily implies a patient exercise of listening, something that our society lacks nowadays. The problem with content circulation is an issue that has driven not only Martínez’ work as an artist but also his career as a music producer and founder of independent labels. Abolipop and Suplex, created alongside his brother, Diego Martínez, are two platforms of distribution and production tan have enriched the independent music scene in Mexico. Their albums and compilations are characterized by betting on content far from commercial circuits. The number “666” of this piece seems, therefore, like a wink to countercultural and resistance movements. Finally, as any other music library, the installation works as a mirror: the piled cassettes and the sheets of paper with the typed index become some sort of selfportrait of the artist. Text by Esteban King

|

|